- Home

- Holeman, Linda

The Saffron Gate Page 2

The Saffron Gate Read online

Page 2

‘Hotel Continental, s’il vous plaît,’ I told him, because I knew no other name, and he nodded once, putting out his hand, palm up, as he quoted me a price in French sous.

I thought of the portly American’s warning words: North Africa is a place where one must keep one’s wits about one at all times. What if this man, nodding so quickly, had no intention of taking me to the hotel? What if he were to take me to some hidden spot and leave me, driving away with my money and my bags?

Or worse.

The enormity of what I had done — travelling here, with no one to call upon should I need assistance — came over me again.

I looked at the man, and then at the milling crowds of other men. Some of them looked at me openly, and others hurried by, heads down. What choice did I have?

I licked my lips and named half the price the small man had asked for. He slapped his chest, frowning, shaking his head, speaking again in the unknown language, and then named another price in French, halfway between his first offer and mine. He didn’t meet my eyes, and I didn’t know whether this was because he was shy or shifty. Again I thought of the risk of putting my faith in him, and again argued with myself. I was almost woozy with the heat, and knew I couldn’t carry my own luggage more than a few steps at a time. I reached into my bag and pulled out the coins. As I placed them on the man’s palm I saw, with a small start of surprise, that there was a fine line of dirt under my fingernails.

It appeared that this dark continent had become a part of me from my very first footsteps on its soil.

The man lifted my two bags into the open back of the cart with amazing ease. He gestured to the seat beside him, and I climbed up. As he lightly slapped the reins against the donkey’s back and the cart rolled forward with a jerk, I took another deep breath.

‘Hotel Continental,’ the man said, as if confirming where we were going.

‘Oui. Merci.’ I answered, glancing at his profile, and then stared straight ahead.

I had arrived in North Africa. There were many miles still to travel, but at least I had made it this far — to the beginning of the last part of the long voyage.

I was in Tangier, and the architecture, the faces of the people and their language and clothing, the foliage, the smells, the very air itself, were all foreign. There was nothing to remind me of home — my quiet home in Albany in upstate New York.

And as I looked back towards the ferry, I knew also that there was nothing left for me in America — nothing and no one at all.

TWO

I had been born on the first day of the new century, 1 January 1900, and my mother named me Sidonie, after her grandmother in Quebec. My father had wanted Siobhan, in remembrance of his own mother, long buried under Irish soil, but he acquiesced to my mother’s wishes. Apart from their shared religion, they were an unlikely match, my lanky Irish father and tiny French-Canadian mother. I was born late in their lives; they had been married eighteen years when I arrived, my mother thirty-eight and my father forty. They had never expected to be so blessed. I heard my mother give thanks for me every day in her prayers, calling me her miracle. When she and I were alone we spoke French; when my father entered the room we switched to English. I loved speaking French; as a child, I couldn’t describe the difference between it and English, but my mother told me, when I was older, that I had used the word curly to describe how the French words felt on my tongue.

And as a child I truly thought myself to be a miracle. My parents fed into this belief when I was young: that I could do no wrong, and that anything I wished for might some day come true. They had little to give me in terms of material possessions, but I felt loved.

And very special.

All through the uncharacteristically warm spring of 1916 — shortly after my sixteenth birthday — I imagined myself in love with Luke McCallister, the boy who worked in the feed store on Larkspur Street. All the girls in my class at Holy Jesus and Mary had talked about him since he’d arrived in our neighbourhood a few months earlier.

We argued amongst us who would be the first he would talk to, go for a walk with, or share an ice cream with.

‘It will be me,’ I told Margaret and Alice Ann, my best friends. I had imagined the scene in my head over and over. Surely it wouldn’t be long before he became aware of me. ‘I’ll make him notice me. You watch.’

‘Just because you always have the most dance partners doesn’t mean you can have all the attention whenever you want, Sidonie,’ Margaret said, her chin lifted.

I smiled at her. ‘Maybe not. But …’ I brushed my hair back with my fingers, running a few steps ahead of them and turning to walk backwards, facing them, my hands on my hips. ‘We’ll see,’ I added. ‘Remember Rodney? You didn’t believe me when I said I’d get him to take me on the Ferris wheel at the fair last year. But I did, didn’t I? He didn’t choose any other girl but me. And we went twice.’

Alice Ann shrugged. ‘That’s just because your mother is friends with his mother. I’ll bet Luke talks to Margaret. Especially if she wears her pink dress. You’re beautiful in pink, Margaret,’ she added.

‘No, it will be you, Alice Ann,’ Margaret said, obviously pleased by Alice Ann’s comment.

‘Think what you will,’ I said, laughing now. ‘Think what you will. But he’ll be mine.’

They laughed with me. ‘Oh, Sidonie,’ Alice Ann said. ‘You always say the silliest things.’ She and Margaret caught up with me then, and we linked arms and leaned against each other as we walked along the narrow street, our hips and shoulders touching as we matched our steps.

The three of us had been best friends since the first grade, and they always counted on me to tease and surprise them.

I found many reasons to walk down Larkspur Street, waiting for Luke to glance in my direction as he tossed huge, heavy bags of grain with apparent ease. I rehearsed what I would say to him, commenting on how strong he must be to make the bags look as though they contained nothing but feathers. I stole glances at him, imagining what his gleaming muscles would feel like under my hands, on top of my body.

I knew, from the lectures of the sisters at Holy Jesus and Mary, that the desires of the flesh were evil, and must be fought against, and yet I seemed as powerless to stop them as I was to change the predictability of the seasons.

One steamy Sunday at the beginning of June, at Our Lady of Mercy church, I prayed so hard to the Virgin Mother for Luke to fall in love with me that I was suddenly overcome with a strange sense of leaving my body. My neck had been stiff that morning when I awoke, my head aching to such a degree that my stomach churned. I begged my mother to let me stay home, but she refused.

It wasn’t uncommon for me to try to find a way to avoid church.

As we walked the mile and a half to Our Lady, my mother admonished me, more than once, to keep up, but it seemed as though I was walking through water, the current making it difficult to move easily. Once inside the dim church, the light filtering through the stained glass made a strange yet beautifully illuminated spinning vortex whenever I moved my eyes.

My body, usually light and quick, was heavy and cumbersome as I knelt alongside my mother, and it was then, with my own fingers interlaced, that everything grew confused: the rosary clicking between my mother’s swollen fingers appeared to be dozens of small moving creatures, the smell of the incense was overpowering to the point of making me more nauseous, and the incantations of Father Cecil were as garbled as though he spoke in other tongues. It hurt the back of my neck to lower my chin to pray, and so instead I stared at the saints along the walls, pious and tormented in their narrow niches. Their marble skin glowed, alabaster and pearl, and when I looked at the Holy Mother I saw tears, like glass, on her cheeks. The Virgin’s lips parted, and I leaned forward, my chin on my arms on the back of the pew in front of me, my knees numb on the stone floor.

Yes, Mother, yes, I begged, tell me what to do. Tell me how to make Luke love me. What can I do to make him want me? I beseech you, Holy Mother. Te

ll me.

I had to close my eyes against the sudden brilliant light in the church, but on the insides of my eyelids. I saw the Virgin Mary reach her arms to me. And then, effortlessly, I was flying towards her. I soared over the nave and the confessional, the rows of pews, the altar boys, the candles. There was Father Cecil at the pulpit, with his slightly humped back under his robe, and the bowed heads of the congregation. And then I saw my own body, slumped oddly to one side. The church glowed in beatification, white and shimmering. I knew the Holy Mother had heard my prayer, and had deemed that yes, I deserved this wish. She would answer my prayers.

She let me see Luke’s face, and then I was no longer flying but falling, unafraid, for my body was as free as the wild rose petals that rain down with the evening wind. I was falling as slowly as a diamond through still water, or a star trailing through a dark and lustrous sky. I was falling towards Luke, who put out his arms to catch me, a gentle smile on his beautiful mouth.

I smiled back at him, my lips parting to touch his, and the colour and heat and light all became one, and I was overcome with a rapture I had never known.

When I awoke, I was in my own small bedroom. The light was still too bright; it hurt my eyes when I blinked, trying to focus.

A woman in a white dress stood near the window, humming my favourite lullaby. I hadn’t heard it since I was a child. Dodo, I’enfant, do. Sleep, child, sleep.

I thought it was another vision of the Virgin Mary, singing the French song my mother had sung to soothe me when I was small. Then the woman stepped away from the window and bent over me, and I saw, with dull surprise, that it was only my own mother. But there was something wrong with her face; she looked different, so much older. I felt, for one moment, that I must have slept through months or even years.

‘Ah. Ma petite Sido,’ she said, and her voice was as unfamiliar as her face. It was thick in her throat, as if she spoke through flannel.

I tried to open my lips, but they were stuck together. My mother gently swabbed them with a damp cloth, and then held a straw to my mouth. ‘Come, drink,’ she said, and I drank, the liquid so cold and somehow fragrant that it seemed to me I had never before tasted water.

But the effort of simply swallowing was so great that I had to close my eyes. I must have fallen asleep again, for when I next blinked, the light in the room had changed, and was softer, shadowed, and I could see more clearly. My mother still — or again — stood over me, but now, strangely, my father was at the open window, looking in.

‘Dad?’ I whispered. ‘Why are you outside?’

His face folded in on itself, his chin quivering in the oddest way. I suddenly realised he was crying. He put his hand on his forehead in a gesture that looked like defeat.

‘What’s wrong?’ I asked, carefully moving my eyes from him to my mother, and finally back to my father.

‘It’s the infant paralysis, my girl,’ he said.

I tried to make sense of it. I wasn’t an infant. Paralysis I understood, and although the word sent a shiver of horror through me, I was too weak to do more than close my eyes again.

That summer, the polio epidemic of 1916 raged through the state of New York. Although the doctors could identify it, there seemed to be no prevention or cure. Most of those who contracted it were children under ten; some, like me, were older. Nobody knew where it had started, although eventually I heard that many believed it was brought in by immigrants.

So many died. And I was told, by my parents, that I was one of the lucky ones. It’s another miracle, my mother had whispered into my ear, the first day I understood fully what had happened to me. Another miracle, as you were, Sidonie. We must pray to give thanks.

It was well known that polio was contagious; I was in quarantine. My mother stayed with me, for she had been with me when I fell ill. But my father didn’t enter our house again for a number of weeks; he needed his job, chauffeur to one of the wealthy families who lived throughout our county.

Margaret and Alice Ann and other friends from school left small presents — a book, a stick of striped candy, a hair ribbon — on our porch, at the foot of the door marked with a paper from the state to indicate the quarantine. For those first weeks my mother kept saying that soon I would be better, that the strength would return to my legs. It was only a question of time, she said. She followed the recommendations given out by the health service nurse, agreed upon by the doctor who had come to see me. She daily bathed my legs in almond meal. She made endless poultices of camomile, slippery elm, mustard, and other nasty-smelling oils, putting the hot plasters on my legs. She massaged my thighs and my calves. When I found the strength to sit up for a few moments, she pulled my oddly heavy legs to the edge of the bed, and put her arm around my waist, trying to help me stand, but it was as if my legs didn’t belong to me. They wouldn’t support me, and I wept with anger and frustration.

‘When will they be better?’ I kept asking, expecting that I would simply wake up one morning, throw back the covers, and walk briskly across my bedroom as usual.

My mother murmured, ‘Soon, Sido, soon. Remember how you ran about the yard as a little girl, pretending you were a princess, like the ones in your books? How you twirled about, your dress billowing around you like a beautiful flower? You will be this again, Sidonie. A princess. A beautiful flower. My beautiful special flower, my miracle.’

The fact that her eyes filled as she said these things only made me believe in her conviction.

For the first few months I wept often — tears of impatience, tears of disappointment, tears of self-pity. My parents were sympathetic and did what they could — in both word and deed — to make me feel better. It was a long time before I could understand what an effort this was for them: to put on a positive face and attitude when they must have been as shattered and grieving as I was.

After some time I grew weary of my own burning eyes and the headaches brought on by the crying, and one day I simply stopped, and didn’t cry again. When the quarantine had passed and I felt well enough, my friends came to see me. It was the beginning of the new school year, and during those initial visits, when my life felt like a strange, disturbing twilight from which I couldn’t quite awaken, I listened to their stories, nodding and imagining myself back in school with them.

Every Friday my mother picked up my schoolwork from Holy Jesus and Mary, and returned it the following Friday; with the aid of the textbooks I was able to complete the weekly assignments and tests.

One Friday, along with my new assignments, my mother handed me a sealed envelope from one of the sisters who had formerly taught me. When I opened it, a letter and a small prayer card, edged in gold, fell from its folds on to the blanket.

The sister’s writing was difficult to read, the script small and tight, as though each black letter was painfully forced through the nib of the pen.

My dear Sidonie, I read. You must not despair. This is God’s will. You have been predestined for this test. It is simply a test of the flesh; God found you wanting, and so chose you. Others have died, but you have not. This is proof that God has protected you for a reason, and has also given you this burden, which you will carry for the rest of your life. In this way, He has shown you that you are special to Him.

As a cripple, now God will carry you, and you will know Him with a strength that those with whole bodies do not.

You must pray, and God will answer. I will also pray for you, Sidonie.

Sister Marie-Gregory

My hands were shaking as I folded the letter and put it and the prayer card back into the envelope.

‘What is it, Sidonie? You’ve gone pale,’ my mother said.

I shook my head, carefully placing the envelope between the pages of a textbook. As a cripple, the sister had written. For the rest of your life.

Even though Sister Marie-Gregory had also said that I was special to God, I knew, with a sickening thud of reality, that it didn’t mean, as my mother told me, that He would let me walk again. But I also

knew that the polio wasn’t a test sent by God, as the sister had said. I alone knew why I had contracted the disease. It was punishment for my sinful thoughts.

Since Luke McCallister had come to Larkspur Street I had stopped praying for forgiveness for my own, transgressions. I no longer sent healing thoughts for others in our community who were ill or dying. I had not prayed for the end of the Great War. I had not prayed for the starving brown children of far-away lands. I had not prayed for my mother’s hands to know relief from their endless ache, or for my father to be able to sleep without the old and haunting nightmares of the coffin ship that had brought him to America.

Instead I had prayed for a boy to take me in his arms, to put his mouth on mine. I had prayed to know the mystery of a man’s body against mine. I had explored my own body with its unexplained heat and desire, imagining my hands were Luke McCallister’s. I had committed one of the seven cardinal sins — lust — and for this I was punished.

A week after the sister’s letter, I was again visited by the doctor from the public health services. This time I was alert, as I hadn’t been on his first call, and read on his face that he had seen far too many victims of polio in too short a time. Openly weary and speaking with a sighing resignation, he agreed, after moving my legs about and testing my reflexes and having me try a few simple exercises, with Sister Marie-Gregory’s written prediction. He told me, my parents standing behind him, their faces grey with sorrow, that I would never again walk, and the best I could hope for was that I would spend my life in a pushchair. He told me I should be grateful the disease had only affected my lower limbs, and that I was better off than many of the children left alive but totally paralysed by the epidemic.

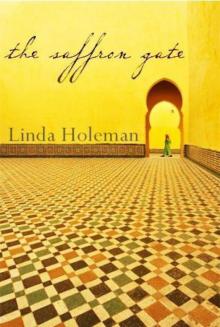

The Saffron Gate

The Saffron Gate